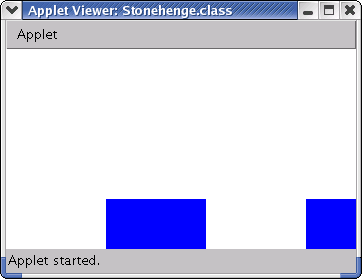

Your job is to modify your program so that it gives a more accurate,

though still boring,

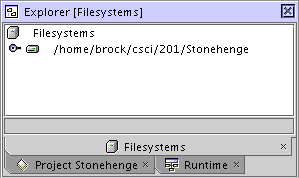

rendition of Project Stonehenge, as shown below.

You improve Stonehenge by

adding two rectangles to the applet. To help you out,

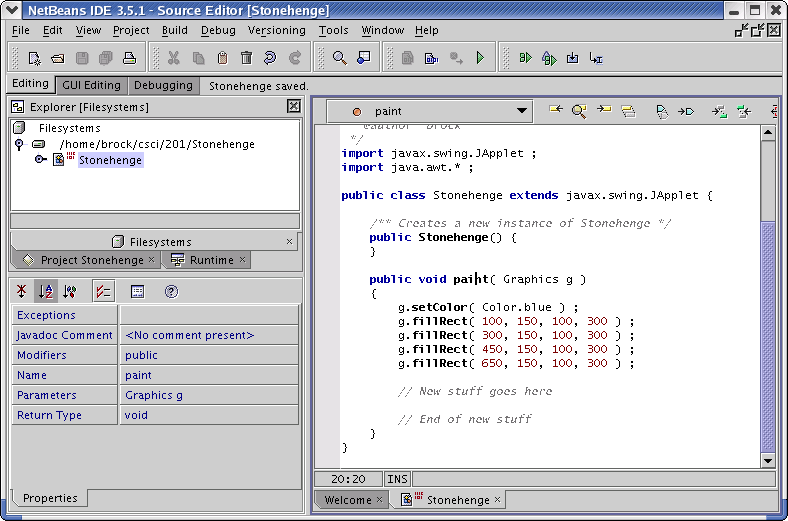

let's talk a little about your present Java file. The file

starts by importing classes from two packages, the class JApplet

from the package javax.swing, and all classes from the package

java.awt.

We need the classes in the package java.awt to draw

objects.

We need the JApplet class so we can extend it.

Notice the line of code:

public class Stonehenge extends JApplet {

This is where we tell the compiler that our applet is called

Stonehenge and that it will be a subclass of

the JApplet class which it

is itself a subclass of the Applet class.

JApplet is an updated version of

the Applet class that uses the new Java Swing interface. Since web

browsers are written to load any applet, you should be able to run

Stonehenge in any up-to-snuff browser.

Our applet contains only one method. This method is

not main()

Applets do not need a main() method because their

execution is controlled by the Web browser.

When we write an

applet, we need to define a paint() method which

is responsible for creating the applet display. This method always receives

a single parameter, a Graphics

object. We can give the parameter any name we choose, but it this case we

have named it simply g.

We use methods belonging to this Graphics object

to render text and shapes in our applet display.

Let's take a look at the Graphics object's methods that we use in the

body of paint().

public void paint(Graphics g) {

g.setColor( Color.blue ) ;

g.fillRect( 100, 150, 100, 300 ) ;

g.fillRect( 300, 150, 100, 300 ) ;

g.fillRect( 450, 150, 100, 300 ) ;

g.fillRect( 650, 150, 100, 300 ) ;

First we set the color to blue with

g's setColor() method,

giving it the object Color.blue as input. Then we draw

rectangles and fill them with our chosen color

using the method fillRect(). This method has four

parameters corresponding to the four pieces of input it needs to do

its job. Let's take a look, in order, at the four parameters used in

our first call to fillRect().

g.fillRect( 100, 150, 100, 300 ) ;

- The x coordinate of the upper-left corner of the rectangle which

is 100 pixels from the left edge of the drawing area.

- The y coordinate of the upper-left corner of the rectangle which

is 150 pixels down from the top of the drawing area.

- The rectangle's width which is 100 pixels.

- The rectangle's height which is 300 pixels.

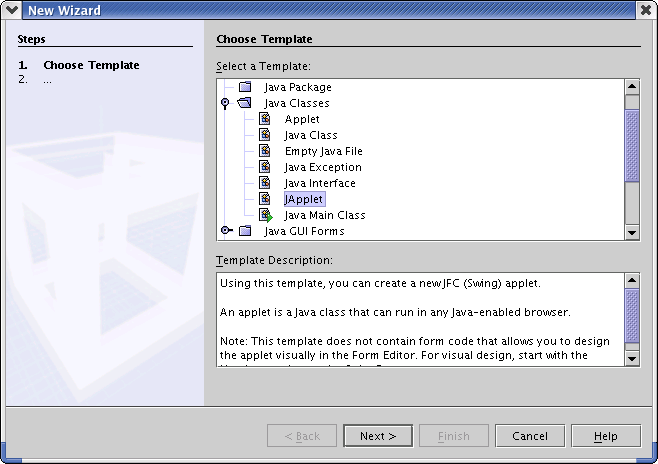

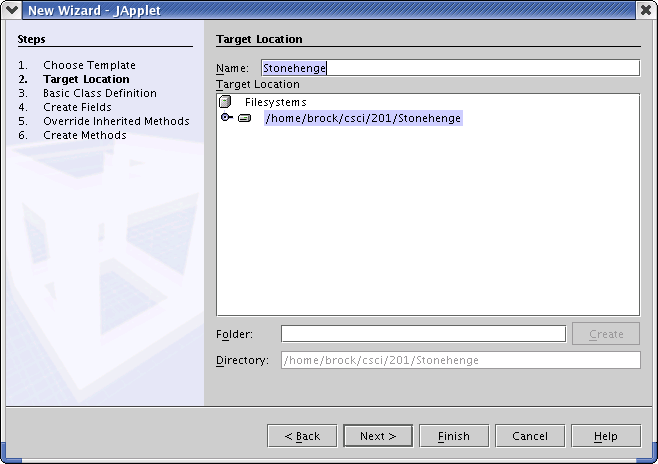

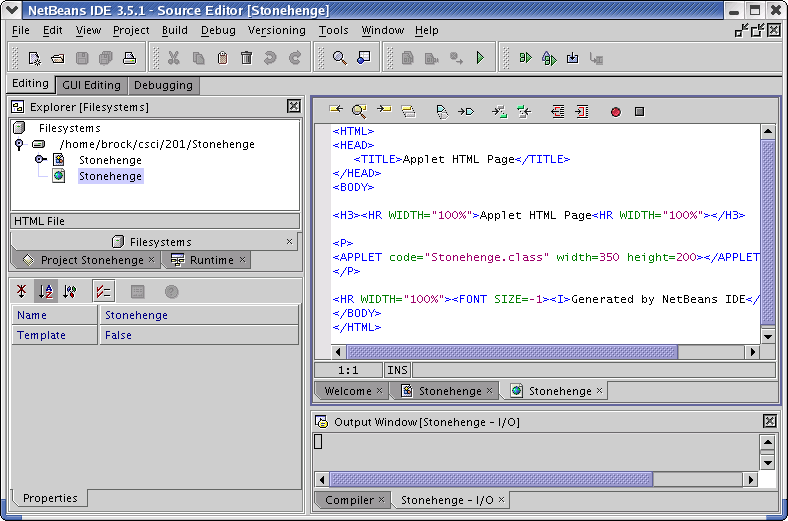

![]() in the menu bar at the top.

This will bring up a list of templates for you to

use to create a file.

Select the Java Classes -> JApplet Template

and then click Next.

in the menu bar at the top.

This will bring up a list of templates for you to

use to create a file.

Select the Java Classes -> JApplet Template

and then click Next.